Disinformation and Propaganda Glossary

Disinformation and Propaganda Glossary

Propaganda is an old concept. The term was first used in 1622 by the Catholics on Congregatio de propaganda de fide (Congregation for the propagation of faith). It has been used in different ways, but nowadays, it is mostly associated with disinformation.

Jowett & O’Donnell's (2013: 7) definition: ”Propaganda is the deliberate and systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist.”

Authors distinguish between white, grey, and black propaganda. They can briefly be described as follows:

Black propaganda means intentional lies. This concept resembles Wardle's concept of disinformation, fabricated and manipulated content (more about Wardle on "disinformation").

Grey propaganda may contain correct facts, but the facts are framed och presented in a misleading way. This resembles some of Wardle's categories, but in Wardle's taxonomy misinformation is not intentional.

White propaganda is pretty much any kind of openly strategic communication, such as advertising, marketing, or well-meaning campaigns like "Stop smoking." Critics, however, point out that if anything can be classified as propaganda, the concept loses its meaning. Wardle doesn't include this type of content.

The point is that strategic communication can take many different forms and be used for many different purposes. Obvious lies are easier to detect than more subtle attempts to shape perceptions or behavior. Some attempts at persuasion may be positive (for example, health campaigns), and some negative (disinformation campaigns).

Jowett, G. S. & O'Donnell, V. (2013). Propaganda and Persuasion. Sage.

Wardle, C. (2018). The Need for Smarter Definitions and Practical, Timely Empirical Research on Information Disorder, Digital Journalism, 6:8, 951-963, DOI: 10.1080/21670811.2018.1502047.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

Ad temperantiam |

The argument to moderation is a logical fallacy that assumes the truth must lie between two opposing viewpoints. This fallacy does not necessarily claim that seeking a middle ground is always wrong, but it applies when the middle position is ill-informed, unfeasible, or impossible, or when an argument claims correctness simply because it is a compromise. The argument to moderation fallacy occurs when it is assumed that the truth must be found between two extremes. While compromise and finding middle ground can sometimes lead to reasonable solutions, this fallacy misleads by suggesting that the middle position is always the correct one. In reality, the truth might align entirely with one of the extremes or lie outside the given spectrum of positions altogether. Recognizing this fallacy helps in evaluating arguments based on their merits and evidence rather than arbitrarily assuming that the middle ground is inherently valid. |

Ad verecundiam |

An expert asserts A is true. Therefore A is true. The expert, of course, may not be expert, but they are a touchstone that people use to avoid having their own expertise challenged. You can also assert your own expertise. If the other person cannot challenge your credentials, then they cannot challenge your argument. The dilemma with this appeal is not so much in the assertion of truth but in the true expertise of the so-called expert, who may be guessing or even joking. It is also known that if you bring together a group of experts then you are likely to get less than full agreement about any given question. The expert may not be named (and is hence an anonymous authority) or may be absent and unable to answer probing questions. In this case, it is not known whether the person quoting the expert is quoting them accurately or even making the whole thing up. Appeal to authority is a common method used in confidence tricks, where the confidence trickster sets themself up as an authority and so both dissuades the target from asking questions and encourages them to trust their 'expert' judgement. |

Affirming the consequent |

In propositional logic, affirming the consequent is a formal fallacy. It occurs when someone takes a true conditional statement and incorrectly infers its converse. This means assuming that if "If A then B" is true, then "If B then A" must also be true, which is not necessarily correct. This fallacy assumes that an if...then... statement is reversible. Specifically, it mistakenly believes that given "If A then B," it can also be true that "If B then A." In this context, B (the 'then' part) is called the 'consequent,' and A (the 'if' part) is called the 'antecedent.' Examples:

|

Agenda setting |

Agenda setting means the "ability [of the news media] to influence the importance placed on the topics of the public agenda". If a news item is covered frequently and prominently, the audience will regard the issue as more important. |

Amphiboly |

The structure of a sentence has more than one possible meaning. Syntactic ambiguity is characterized by the potential for a sentence to yield multiple interpretations due to its ambiguous syntax. Examples:

|

Argumentum ad infinitum |

The fallacy of dragging the conversation to an ad nauseam state in order to then assert one's position as correct due to it not having been contradicted is also called argumentum ad infinitum (to infinity) and argument from repetition. |

Argumentum in terrorem |

Appeals to fear seek to build support by instilling anxieties and panic in the general population. An appeal to fear is a fallacy in which a person attempts to create support for an idea by attempting to increase fear towards an alternative. This fallacy has the following argument form:

|

Assertion |

The mere fact of asserting a truth makes it true. "I say that X is true. Therefore X is true." Being assertive is an adult way of behaving, stepping off the passive-aggressive continuum and stating a truth with conviction. This can be a very persuasive position, as it removes aggressive threat without capitulation, demonstrating maturity and apparent wisdom. Assertion is often a veiled appeal to authority in that it makes the assumption that the person making the assertion is an expert or has a position of unassailable formal authority. |

Astroturfing |

Is the practice of hiding the sponsors of a message or organization (e.g., political, advertising, religious, or public relations) to make it appear as though it originates from, and is supported by, grassroots participants. It is a practice intended to give the statements or organizations credibility by withholding information about the source's financial backers. The implication behind the use of the term is that instead of a "true" or "natural" grassroots effort behind the activity in question, there is a "fake" or "artificial" appearance of support. The term astroturfing is derived from AstroTurf, a brand of synthetic carpeting designed to resemble natural grass, as a play on the word "grassroots". |

Biased sample |

In statistics, sampling bias is a bias in which a sample is collected in such a way that some members of the intended population have a lower or higher sampling probability than others. It results in a biased sample of a population (or non-human factors) in which all individuals, or instances, were not equally likely to have been selected. If this is not accounted for, results can be erroneously attributed to the phenomenon under study rather than to the method of sampling. Sample X is taken from Population Y. Conclusion Z is drawn from sample X. It is assumed that Z is also true about Y. Take a biased or otherwise statistically invalid sample. Analyze the data. Draw conclusions and declare the results significant. |

Conspiracy theory |

A is true. B is why the truth cannot be proven. So A is true. Make a statement. Then explain why it cannot be proven. Accuse anyone who challenges the second statement of trying to cover up the truth. Use this attempt as proof that the original statement is true. Examples:

This fallacy works by making it impossible to challenge the proving statement without proving it. The focus of attention is thus moved to the person trying to disprove the 'proof', and reframes their refutation as further proof. |

Cum hoc ergo propter hoc |

The idea that "correlation implies causation" is an example of a questionable-cause logical fallacy, in which two events occurring together are taken to have established a cause-and-effect relationship. Examples:

|

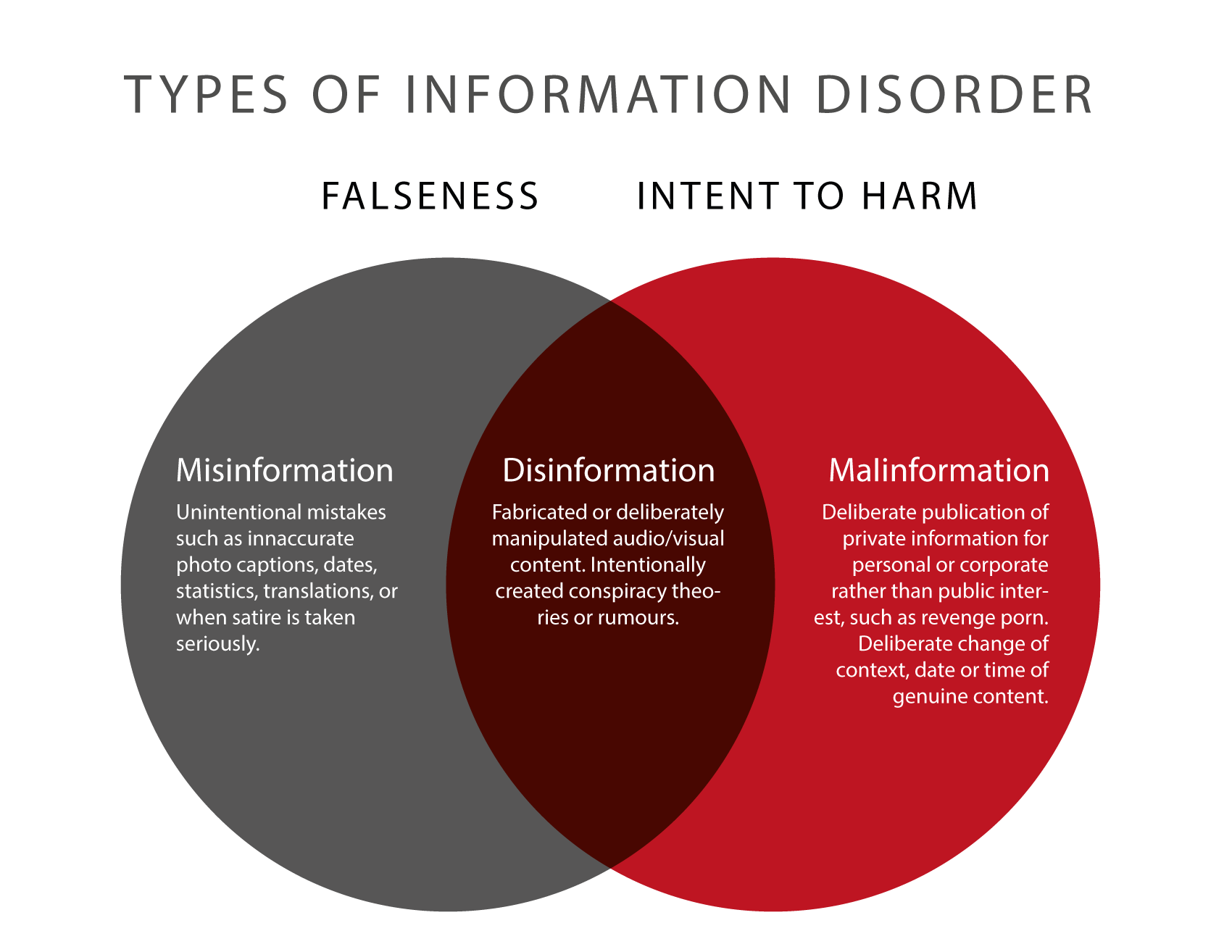

Disinformation, misinformation |

Wardle (2017) makes a distinction between misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation.

|

Equivocation |

An informal fallacy resulting from the use of a particular word/expression in multiple senses within an argument. It is a type of ambiguity that stems from a phrase having two or more distinct meanings, not from the grammar or structure of the sentence. Example: Since only man(human) is rational. |

False analogy |

A false analogy is a logical fallacy that occurs when an argument is made based on misleading, superficial, or inappropriate comparisons. It asserts that because two things are alike in one or more respects, they are necessarily alike in some other respect, even though this is not supported by the facts. Examples:

|