Targeting the fundamental infrastructure supporting democratic elections, cyberattacks provide Russia with a smart and covert weapon in its armory. These attacks range from hacking into voter databases to interfering with electoral commission activities and exposing private data to damage politicians and organizations. The ultimate goal is to destabilize political systems and advance Russia’s geopolitical interests.

In this second part of our series (see part 1 here), we will discuss the various cyberattack methods employed by Russia. We will explore how these cyber operations are executed, their impact on security in general, not just the impact on elections, and the broader implications for global democracy.

A recent example shows the severity of this threat. On the first day of the 2024 European elections, a pro-Kremlin hacker group targeted the websites of at least three Dutch political parties. The Christian Democratic Appeal, the Party for Freedom, and the Forum for Democracy reported cyber-attacks, with Thierry Baudet, leader of the Forum for Democracy, confirming the attack on social media. Similarly, the website of Geert Wilders' Party for Freedom was rendered inoperable.

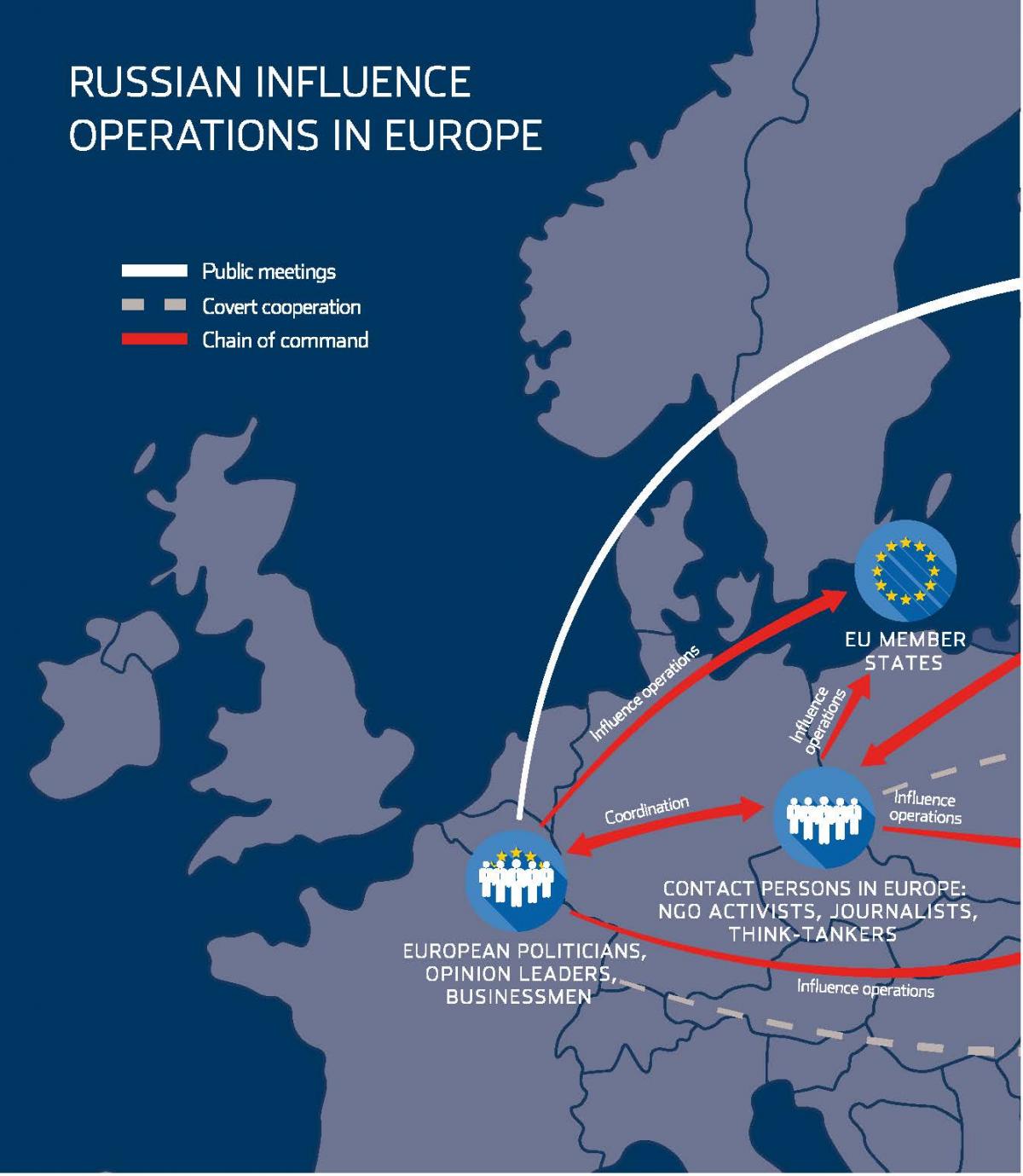

This coordinated attack, claimed by the hacker group HackNeT on their Telegram channel, not only affected political parties but also targeted EU institutions, including the European Court of Auditors. These incidents occurred amid growing concerns about the susceptibility of the largest transnational election in history to foreign subversion. EU officials, aware of the critical nature of the 72 hours leading up to the vote, had mobilized rapid alert teams to counter such threats, including disinformation and cyber-attacks (Euronews, 2024).

In 2023, the UK and its allies have also exposed a series of cyber operations by Russian Intelligence Services targeting high-profile individuals and entities. The UK Government assesses that these actions were intended to interfere with UK politics and democratic processes.

Centre 18, a unit within Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), has been identified as responsible for various cyber espionage activities targeting the UK. These operations were conducted by Star Blizzard, a group almost certainly subordinate to FSB Centre 18, as evaluated by the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). Known by other names such as Callisto Group, SEABORGIUM, and COLDRIVER, Star Blizzard is operated by FSB officers and has selectively leaked information to undermine trust in UK politics and other democratic states.

A few incidents that have been exposed by the UK Government:

Targeting of Parliamentarians:

Since at least 2015, Star Blizzard has targeted members of multiple political parties through spear-phishing attacks.

Hacking of UK-US Trade Documents:

The 2019 leak of UK-US trade documents, ahead of the UK General Election, was previously attributed to the Russian state and is linked to Star Blizzard’s activities.

Institute for Statecraft Attack:

In 2018, the Institute for Statecraft, a UK think tank, was hacked, with subsequent leaks of documents. More recently, in December 2021, the account of its founder Christopher Donnelly was compromised.

Targeting of Various Sectors:

Star Blizzard has also targeted universities, journalists, public sector organizations, NGOs, and other civil society groups extremely important to UK democracy.

Following an investigation by the National Crime Agency, the UK has sanctioned two members of Star Blizzard, in coordination with the US, for their roles in spear-phishing campaigns and unauthorized data exfiltration intended to undermine UK institutions. The US Department of Justice has concurrently unsealed indictments against these individuals.

The sanctioned individuals are:

- Ruslan Aleksandrovich Peretyatko: A Russian FSB intelligence officer and member of Star Blizzard.

- Andrey Stanislavovich Korinets (AKA Alexey Doguzhiev): Another member of Star Blizzard.

These incidents are part of a broader pattern of Russian malign cyber activities that include high-profile cases like ViaSat, SolarWinds, and attacks on Critical National Infrastructure.

Election Interference by Russia…and China + Iran

Intelligence officials have warned that China, Russia, and Iran possess the capabilities and intent to disrupt the upcoming 2024 US presidential election. This revelation comes as the intelligence community prepares to brief members of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence at the annual Worldwide Threats hearing on March 11, 2024 (NextGov, 2024).

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) released its annual threat assessment, compiling insights from various US spy agencies. This assessment highlights the cyber and technological threats posed by foreign adversaries to U.S. national security, focusing on the upcoming elections.

Threats from China, Russia, and Iran

China: The assessment indicates that China may attempt to influence the election to sideline critical views of the Chinese government and amplify societal divisions within the U.S. This could include the use of state-run TikTok accounts targeting candidates, as observed during the 2022 midterms. Even without direct orders from Beijing, individuals aligned with Chinese interests might engage in election interference.

Russia: Moscow sees the 2024 elections as an opportunity to influence outcomes that would benefit its geopolitical interests, particularly concerning US support for Ukraine. Russia is expected to deploy various influence operations to affect the elections in ways that align with its goals.

Iran: Iran has a history of conducting influence operations aimed at U.S. elections and is likely to continue such efforts. Recently, Iranian-linked hackers targeted U.S. water treatment plants, highlighting their capability to execute disruptive cyberattacks.

The intelligence community's assessment also highlights domestic challenges, such as reduced content moderation staff at social media companies, which poses a significant risk to election integrity. Election workers face threats of violence from voters who may not accept polling results, exacerbating the threat landscape.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has not been in touch with social media firms about election security specifics, a gap partly due to a pending Supreme Court case regarding the government's ability to communicate with these companies about disinformation.

Emerging Threats: AI and Robocalling

Officials and researchers express concern that advanced AI tools available on the dark web could enhance hackers' abilities to breach election infrastructure or create convincing disinformation campaigns. An example of this threat was seen in January, when a Texas-linked robocalling operation used an AI-generated voice of President Joe Biden during the New Hampshire primary to mislead voters. This incident led to a Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ban on using AI voices in robocalls within the US.

Cyber Warfare in the Russia-Ukraine Conflict

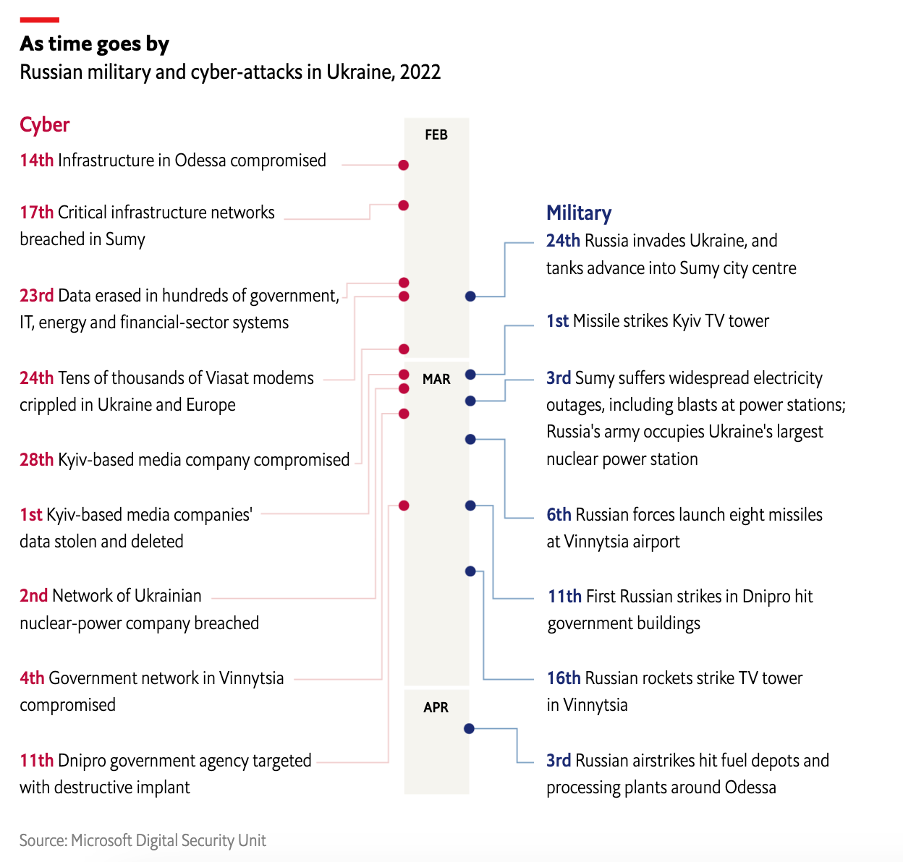

The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine has highlighted the extensive use of cyber warfare as a tool for geopolitical influence. Since the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia has launched persistent cyberattacks against Ukraine, targeting its public, energy, media, financial, business, and non-profit sectors. These attacks intensified just before the 2022 invasion and have continued throughout the war, disrupting essential services, stealing data, and spreading disinformation, including through deep fake technology.

EU, US, and NATO-led initiatives have been crucial in countering these cyber threats and protecting essential infrastructure. The EU has activated its Cyber Rapid Response Teams to support Ukraine's cyber-defense, while private companies like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google have assisted in detecting and countering cyber-attacks. Independent hackers have also launched counter-attacks, targeting Russian government, media, and financial systems to expose sensitive information and disrupt operations.

Historical Context and Evolution

Russian cyber operations have become increasingly sophisticated and pervasive, posing significant threats to global democratic processes. The following information is based on the 2021 report Russian Cyberwarfare: Unpacking the Kremlin’s Capabilities by Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, published by the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA).

The roots of Russia's cyber command-and-control systems trace back to the Soviet Union's signals intelligence (SIGINT) bureaucracy. Over the decades, these capabilities have evolved significantly, especially under the leadership of various state and non-state actors. Key developments include:

- 1990s: The establishment of the Federal Agency for Government Communications and Information (FAPSI), which played a crucial role in cyber operations and was later split between the FSB, SVR, and FSO.

- 2000s: The rapid expansion of the FSB's cyber capabilities, with the formation of specialized centers like the Information Security Center (TsIB) and the 16th Center, focusing on electronic intelligence.

- 2010s: The institutionalization of information security as a critical area of study in Russian universities, further bolstering the recruitment and training of cyber specialists.

Russia's cyber landscape is characterized by a complex interplay of various actors, each playing a distinct role in cyber operations:

- FSB (Federal Security Service): Divided into centers focusing on different aspects of cyber operations, including the 16th Center (Berserk Bear) and the Information Security Center (TsIB). These entities engage in both defensive and offensive cyber activities.

- GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate): Operates military units like the 85th Main Special Service Center (Fancy Bear) and engages in high-profile cyber-attacks against foreign entities, often collaborating with the FSB for recruitment and operational purposes.

- SVR (Foreign Intelligence Service): Focuses on cyber espionage and has expanded its capabilities significantly in recent years.

- Private Cybersecurity Companies: Play a dual role in both supporting state operations and developing offensive cyber tools. These companies are deeply integrated into the state’s cyber strategy, providing expertise and aiding in recruitment efforts.

Notable Cyber Operations

Russian cyber actors have been implicated in numerous high-profile cyber incidents aimed at influencing political processes and elections:

- 2016 US Presidential Election: The GRU's involvement in hacking and leaking Democratic National Committee emails, which significantly impacted the election's outcome and triggered a major crisis within the US intelligence community.

- 2014 Ukrainian Presidential Election: Cyber-attacks aimed at manipulating vote counts and disrupting the election process, showcasing the strategic use of cyber tools to influence geopolitical outcomes.

- Recent European Elections: Coordinated cyber-attacks on political parties and EU institutions, highlighting ongoing efforts to undermine democratic processes across Europe.

The threat of cyber interference in elections remains a pressing concern, with intelligence assessments warning of potential disruptions in upcoming elections by state actors like China, Russia, and Iran. The use of sophisticated cyber tools and techniques, such as AI-generated misinformation, poses a growing challenge to election security and integrity.

The report "Russia’s Strategy in Cyberspace" published by the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence in June 2021 states that the Russian strategy in cyberspace is deeply rooted in its broader concept of "information confrontation," which is a continuous struggle for influence on a global scale. Unlike the Western approach that often distinguishes between war and peace, Russia views this confrontation as ongoing, utilizing various tools, such as cyber operations, to achieve its strategic goals. Russia's cyber capabilities have evolved significantly over the past few decades. Their evolution is evident in the series of high-profile cyberattacks attributed to Russian state actors over the years.

For instance, in 2014 and 2015, Ukraine experienced several significant cyberattacks aimed at its critical infrastructure and governmental operations. In 2014, just before the Crimean referendum, a DDoS attack disrupted Ukrainian networks to distract from the presence of Russian troops. Another notable incident occurred during the 2015 Ukrainian presidential elections, where pro-Russian hackers attempted to manipulate the vote by targeting the Central Election Commission's network. Although the attack was mitigated just in time, it managed to delay the vote count.

Russia's strategic use of cyber operations is to create instability and uncertainty.The concept of "strategic deterrence" in Russian military doctrine includes not only nuclear and conventional military power but also a wide array of non-military tools such as cyber operations, disinformation, and psychological operations. This comprehensive approach aims to exploit the vulnerabilities of adversaries, often operating below the threshold of open conflict to avoid triggering military retaliation.

The Russian strategy involves targeting both the technical and psychological aspects of information security. Cyber operations are designed to impact the physical infrastructure and also to influence public perception and morale. For instance, operations like the NotPetya attack in 2017 showed Russia's capability to cause widespread disruption while maintaining plausible deniability. This attack, which initially targeted Ukrainian systems, eventually caused collateral damage globally, affecting numerous multinational corporations and government agencies.

We have discussed earlier that Russia's cyber operations are conducted by a complex network of state and non-state actors: The Federal Security Service (FSB), the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), and the military's Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU), which are the primary agencies involved. These entities usually collaborate with private sector experts and cybercriminal groups, which creates a flexible and decentralized operational structure.

To recap: The FSB's 18th Center focuses on domestic security and cyber operations, while the SVR handles international cyber espionage. The GRU, known for its aggressive cyber tactics, has been implicated in many high-profile cyberattacks, including those targeting the US electoral process. This decentralized approach allows Russia to adapt quickly to new opportunities and challenges in the cyber domain. However, it also creates challenges in terms of coordination and accountability, often relying on informal relationships and political expediency to govern cyber operations.

Conclusion and Recommendations by Experts

Cyberattacks form a critical component of Russia's election interference strategy. These attacks target essential electoral infrastructure, including voter databases, electoral commission systems, and private data of political figures and organizations. The objective is clear: to destabilize political systems, undermine public trust, and advance Russia’s geopolitical interests.

Technically speaking, democratic states have to:

- strengthen their cyber defenses against disinformation and cyber threats through better transparency, strong intelligence sharing, and strategic communications integration

- support projects aiming at enforcing data privacy and social media regulation would help to lessen the effects of disinformation campaigns and cyberattacks.

- establish credible deterrents such as public attribution of cyber events and coordinated countermeasures that might discourage adversaries from participating in hostile cyber actions.

Russian cyber activities seriously and continuously endanger the world’s democratic processes. Democratic states can preserve public confidence in their democratic institutions and safeguard the integrity of their elections by realizing the several characteristics of these cyber hazards and putting in place thorough countermeasures. Countering these sophisticated cyber assaults and preserving the future of global democracy will depend much on the alertness and resilience of the democratic society.

References:

https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/06/06/pro-russia-group-claims-responsibility-for-cyber-attacks-on-first-day-of-eu-election

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-exposes-attempted-russian-cyber-interference-in-politics-and-democratic-processes

https://www.nextgov.com/cybersecurity/2024/03/china-russia-and-iran-capable-disrupting-2024-elections-intel-assessment-warns/394850/

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/733549/EPRS_BRI(2022)733549_EN.pdf

https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/russian-cyberwarfare-unpacking-the-kremlins-capabilities/

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/05/10/russia-seems-to-be-co-ordinating-cyber-attacks-with-its-military-campaign