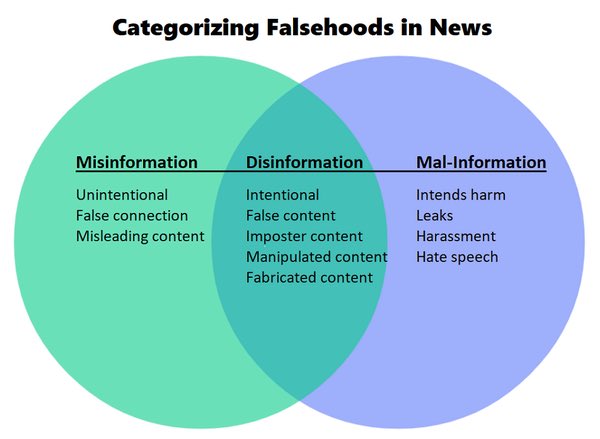

Disinformation is the false, inaccurate, or misleading information deliberately created, presented and disseminated, whereas “mis-information” is false or inaccurate information that is shared unknowingly and is not disseminated with the intention of deceiving the public. Russian action fits squarely with the definition of disinformation.

Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. It differs from disinformation, which is deliberately deceptive and propagated information. Rumors are information not attributed to any particular source, and so are unreliable and often unverified, but can turn out to be either true or false.

Mal-Information refers to information that stems from the truth but is often exaggerated in a way that misleads and causes potential harm.

The effects of misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (MDM) cost the global economy billions of dollars each year. Often known colloquially as “fake news”, MDM are damaging to public trust in institutions and, during elections, may even pose a threat to democracy itself. MDM has become a serious concern for consumers and organizations of all sizes. New technologies such as machine learning, natural language processing, and amplification networks are being used to discredit factual information.

Disinformation campaigns may use artificial intelligence (AI) to spread false and misleading information, such as deepfakes. Deepfakes refer to artificially generated images, audio, and videos used in place of the original image, audio, or video.

How to Identify MDM

Evaluate the information landscape critically and take the time to review the sources and messaging. When viewing content, in any form, ask yourself the following questions. This thread will help you in identifying MDM and implementing the appropriate security measures for mitigation strategies, and take action against MDM. As a consumer of information, you can take these actions to investigate content further and protect yourself from MDM:

- Does it provoke an emotional response?

- Does it make a bold statement on a controversial issue?

- Is it an extraordinary claim?

- Does it contain clickbait?

- Does it have topical information that is within context?

- Does it use small pieces of valid information that are exaggerated or distorted?

- Has it spread virally on unvetted or loosely vetted platforms?

These are a few guiding questions that can help you identify MDM. Even if one of these questions applies to a source, it does not automatically discredit the information. It is an indication to conduct more research on the item before trusting it.

- Information that is valid means that it is factually correct, is based on data that can be confirmed, and is not misleading in any way.

- Inaccurate information is either incomplete or manipulated in a way that portrays a false narrative.

- False information is incorrect and there is data that disproves it.

- Unsustainable information can neither be confirmed nor disproved based on the available data.

- Look for out of place design elements such as unprofessional logos, colours, spacing, and animated gifs

- Verify domain names to ensure they match the organization.

The domain name may have typos or use a different Top Level Domain (TLD) such as .net or .org - Check that the organization has contact information listed, a physical address, and an ‘About Us’ page

- Perform a WHOIS lookup on the domain to see who owns it and verify that it belongs to a trustworthy organization.

WHOIS is a database of domain names and has details about the owner of the domain, when the domain was registered, and when it expires - Conduct a reverse image search to ensure images are not copied from a legitimate website or organization

- Use a fact–checking site to ensure the information you are reading has not already been proven false

- Do not automatically assume information you receive is correct, even if it comes from a valid source (such as a friend or family member)

- Ensure the information is not out of date

- Finally: Consider an approach using Occam’s Razor.

Occam's razor is a principle often attributed to … 14th–century friar William of Ockham that says that if you have two competing ideas to explain the same phenomenon, you should prefer the simpler one.

Fact Checking:

One way to fact-check information is to use reliable sources, such as academic journals, government websites, reputable news outlets, and dedicated fact-checking sites that are signatories to the International Fact-checking Network (IFCN) code of principles. These sources typically have a reputation for providing accurate and reliable information, and they often have a fact-checking process in place to ensure the accuracy of their content.

Another way to fact-check information is to use multiple sources to confirm the accuracy of a statement or piece of information. This can be especially useful when dealing with controversial or disputed topics, as different sources may present different perspectives on the same issue. By comparing multiple sources, it is possible to get a more comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand and to verify the accuracy of the information.

Fact-checking is an essential aspect of journalism and research, as it helps to ensure that the public is provided with accurate and reliable information. By using reliable sources and comparing multiple sources, it is possible to verify the accuracy of the information and protect against the spread of misinformation and disinformation. Fact-checking is also important for individuals and organizations, as it helps to protect their reputation and credibility.

Fact-checking and Verification have since long been crucial skills for journalists even before the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, these two must move hand in hand with journalism in order to ensure that facts and the truth are never buried. But with the current environment characterized by social media platforms and 1.56 billion yearly smartphone unit sales, everyone can attempt to be a journalist. All one needs is an internet connection and they can create or spread the news however they like.

This is partly why the current pandemic is more dangerous than any before. The spread misinformation/fake news on the internet is much faster then the coronavirus itself and some have referred to it as an “infodemic” or “disinfodemic”. We have heard things like “5G spreads the virus”, “children are immune”, “Africans are immune”, “at home remedies such lemon, garlic being proven cures” and plenty more which have been misleading people into disregarding medical advice which is dangerous.

But thankfully, we live in an information environment that empowers everyone to be informed, educated, do research, and a lot more from wherever they are. This is what can help us fight this infodemic. In order to survive this, we must enrich ourselves with fact-checking and verification skills and fully understand fake news, how it develops, and how to fight it. As we all attempt to be journalists online, we should make sure we provide accountable and timely information.

Russian & Chinese Playbooks

The Russian and Chinese playbook on weaponising information

The Russian disinformation narratives are often false, or obscure facts with half-truths and “whataboutisms” (efforts to respond to an issue by comparing it to a different issue that does not engage with the original one). Russian actors employ a diverse strategy to introduce, amplify, and spread false and distorted narratives across the world. Its efforts rely on a mix of fake and artificial accounts, anonymous websites and official state media sources to distribute and amplify content that advances its interests and undermines competing narratives (Cadier et al., 2022).

Russian and Chinese propaganda and disinformation activities are produced in large volumes and are distributed across a large number of channels, both via online and traditional media. The producers and disseminators of this content include paid internet “trolls”, or people who post inflammatory, insincere, or manipulative messages via online chat rooms, discussion forums, and comments sections on news and other websites (Paul and Matthews, 2016). Strategies have also included more targeted approaches.

Similar tactics have continued and expanded during the war, pointing to the ongoing evolution of disinformation approaches and constant need to adapt and respond. The UK Government, for example, found that TikTok influencers were being paid to amplify pro-Russian narratives. Disinformation activities also amplified authentic messages by social media users that were consistent with Russia’s viewpoint in an effort to increase the spread of such narratives, giving an artificial sense of support while evading platforms’ measures to combat disinformation (The Guardian, 2022).

Efforts to manipulate public opinion on social media took place on Twitter and Facebook, with extensive efforts also concentrated on Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.

More overtly, the Russian government runs co-ordinated information (and disinformation) campaigns on its own social media accounts. For example, 75 Russian government Twitter accounts, with 7.3 million followers garnering 35.9 million retweets, 29.8 million likes and 4 million replies, tweeted 1 157 times between 25 February and 3 March 2022. Roughly 75% of the tweets covered Ukraine and many furthered disinformation narratives questioning Ukraine’s status as a sovereign state, drawing attention to alleged war crimes by other countries, and spreading conspiracy theories (Thompson and Graham, 2022).

LinkedIn, Meta, Instagram, Telegram

For its part, LinkedIn has been blocked in Russia since 2016, as the company has chosen not to meet regulatory requirements stipulating that personal information of Russian citizens must be stored on servers in Russia (BBC News, 2016). Almost a month into Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, Russia’s general prosecutor declared Meta an extremist organisation, leading to the banning of Facebook and Instagram in Russia. This action followed the government’s restriction of Twitter earlier in March 2022 (Euronews, 2022).

Immediately prior to the ban, demand for VPNs, which encrypt data and obscure where a user is located, rose more than 2000% compared to the daily average the month prior, suggesting the continued demand for these platforms in Russia (Euronews, 2022). TikTok, a globally popular video sharing platform, has also caused numerous problems for the Russian leadership, as users of the social media platform have revealed troop positions and equipment movements in the lead up to the war (Mamo, 2021; Mackinnon, 2021).

Telegram, a messaging service created by the founder of VKontakte, has also become a means for sharing information among its users, as well as providing a platform for media outlets and journalists to continue their work uncensored. Offering both encrypted and unencrypted chat functionality, its popularity has continued to grow since Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine began, and it has become a source of both independent news and propaganda and disinformation (Allyn, 2022).

According to a poll conducted by the research firm Romir, between February and June 2022, the audience share of Telegram channels in Russia grew by 40% to almost 27% – a higher percentage than for any individual state TV channel (Радио Свобода, 2022). Furthermore, a Levada Centre poll from July 2022 found that while television is still the main news source for 63% of the population, that share has been declining steadily; conversely, reliance on social media as a source of news has increased to 39% of respondents (Левада-Центр, 2022).

Russian propaganda

Russian state control and propaganda:

Beyond the overt efforts to censor specific content, the Russian legal environment is highly unwelcoming to the free press. Private and public media organisations are either owned or run by government-linked individuals and entities. Efforts to control the information space during the current war can also be seen via budgetary spending increases for state media in the run up. Government spending on “mass media” for the first quarter of 2022 was 322% higher than for the same period in 2021, reaching 17.4 billion roubles (roughly EUR 215 million). Almost 70% of Russia’s spending on mass media in Q1 2022 was spent in March, immediately after the invasion (The Moscow Times, 2022).

The outlets that receive these funds, including RT and Rossiya Segodnya, which owns and operates Sputnik and RIA Novosti , are state-linked and state-owned outlets that “serve primarily as conduits for the Kremlin’s talking points”, according to the US State Department (US Department of State, 2022) and can be more accurately thought of as tools of state propaganda (Cadier et al., 2022).

Where audiences previously received information predominantly through Russian state-backed television, the rise of the internet and social media have allowed the Russian government to conduct information operations on a far broader scale at a fraction of the price (Paul and Matthews, 2016). A steady uptake in internet usage (85% of Russians accessed the internet as of 2021 (International Telecommunication Union, 2021) is one motivating factor.

Another, however, is that an online presence has allowed them to reach audiences abroad easily and cheaply. Indeed, on some platforms, Russian state-backed media has likely made money from spreading propaganda. Prior to the war, estimates place the value of advertising revenues on YouTube from RT and other state-affiliated channels at USD 27 million between 2017 and 2018 (and up to USD 73 million between 2007 and 2019) (Omelas, 2019).

As reflected in their budgetary allocations, Sputnik, RT and TASS are among the most influential government/state funded and operated media outlets for spreading disinformation at home and abroad (Statista, 2022; Cadier et al., 2022). RT in particular has seen rapid uptake. In 2013, it became the first news network to surpass 1 billion views on YouTube (Dwoskin, Merrill and De Vynck, 2022). By March 2021, RT DE (the German branch) ranked sixth for most shared media outlet in a study of Telegram groups and channels, ahead of German news publications such as Der Spiegel. Sputnik (known in Germany as SNA), came eighth, while the Russian newspaper Pravda ranked 11th (Loucaides and Perrone, 2021)

References and sources provided in QR Code.

Twitter x penalises threads that provide external links to resources, and prefers accounts publishing unverifiable click bait and un-referenced bollocks, which suits the Russian and Chinese propaganda playbooks.

Please retweet the original post if you enjoyed this - it helps with visibility !

🫶 Support me and keep my work going! But only if you can 🫶

Beefeater is 🇬🇧 Beefeater 🇬🇧 #NAFO #Fella 🇺🇦 The Guardian of Facts 🫶 Beefeater_Fella Twitter and Patreon https://www.buymeacoffee.com/beefeaterfella