Legal and Constitutional Exploitation

One of the most striking features of Hitler’s rise to power was his use of the Weimar Constitution to undermine democracy.

Article 48, which allowed for emergency decrees, became a tool for consolidating power after the Reichstag Fire of February 27, 1933.

Hitler persuaded President Hindenburg to sign the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended civil liberties, allowing the Nazis to arrest political opponents and suppress dissent.

Shortly after, the Enabling Act gave Hitler legislative powers, effectively bypassing the Reichstag.

In the contemporary U.S., democratic erosion has not involved constitutional suspension but has featured legal and institutional exploitation.

For example:

- Executive Overreach: Critics have pointed to the extensive use of executive orders under recent administrations to bypass legislative deadlock.

- Election Denialism: Donald Trump’s refusal to accept the 2020 election results and subsequent attempts to overturn them through lawsuits and lobbying state officials mirrors an effort to delegitimize democratic processes.

While the U.S. Constitution has proven more resilient than the Weimar framework, these events highlight how democratic norms can be undermined within legal boundaries.

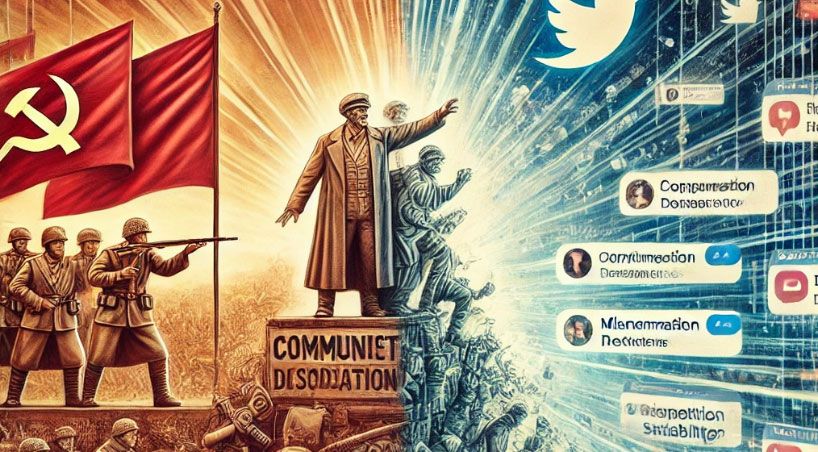

Crisis as a Tool for Consolidating Power

The Reichstag Fire served as a pretext for the Nazis to claim a Communist conspiracy, stoke fear, and justify emergency measures.

Similarly, crises in the U.S. have been leveraged to justify controversial actions:

- The January 6th Capitol attack has been cited as both a symptom and a catalyst of democratic instability. While it did not lead to emergency powers, it underscored how perceived crises can destabilize institutions.

- Representatives of the billionaire class have framed debates about “free speech” on platforms they control as existential threats to democratic discourse. This rhetorical crisis amplifies divisions and may justify curbing dissenting voices under the guise of “balance.”

Though no single crisis in the U.S. has yet served as a turning point akin to the Reichstag Fire, the tendency to weaponize crises for political gain remains a concerning parallel.

Suppression of Opposition and Media Control

In Nazi Germany, the Reichstag Fire Decree allowed for mass arrests of Communists and other political adversaries.

This suppression of opposition was further enabled by strict control of media outlets, ensuring that only Nazi-approved narratives reached the public.

In the U.S., suppression takes subtler forms, particularly through control of digital platforms:

- The acquisition of major social media platforms by members of the billionaire class has raised concerns about how private interests control the public sphere.

- Selective reinstatement of banned accounts and amplification of specific ideologies suggest that these actors can manipulate public discourse.

- Trump’s relationship with right-wing media outlets, such as Fox News, highlights how media ecosystems can echo and amplify political narratives while marginalizing opposition.

While the suppression is not state-driven as in Nazi Germany, the consolidation of media influence by a few powerful actors bears similarity to historical patterns of narrative control.

Economic Elites and Their Role in Politics

During Hitler’s rise, industrialists such as Krupp and Thyssen supported the Nazis, seeing them as a bulwark against Communism and a path to economic stability.

Their funding and influence helped legitimize Hitler’s regime.

Today, representatives of the billionaire class wield outsized influence over politics and policy.

Their ventures into social media, space exploration, and other sectors position them as quasi-political figures whose economic power transcends traditional boundaries. Similarly:

- Campaign donations from billionaires and corporations shape political agendas.

- Lobbying efforts by tech companies influence legislation on antitrust, labor, and data privacy.

While these modern elites do not explicitly align with authoritarian regimes, their disproportionate influence raises questions about the erosion of democratic equality.

Public and Institutional Response

A critical difference between the Weimar Republic and the U.S. lies in societal and institutional responses.

In Weimar Germany, weak institutions and public apathy enabled Hitler’s rapid consolidation of power. In contrast:

- U.S. institutions have shown resilience, as evidenced by the judiciary’s rejection of Trump’s election lawsuits and the peaceful transfer of power in 2021.

- Grassroots movements, such as pro-democracy advocacy and voter mobilization efforts, act as counterweights to authoritarian tendencies.

However, polarization and distrust in institutions remain vulnerabilities that could be exploited further.

Key Differences and Broader Questions

While the historical parallels are striking, differences between 1930s Germany and the contemporary U.S. should not be overlooked:

- The Weimar Republic (1919–1933) was a young, fragile democracy, whereas the U.S. has a long-standing constitutional framework.

- Economic conditions differ significantly; Germany faced hyperinflation and mass unemployment, while the U.S. contends with inequality and a technology-driven economy.

Nevertheless, this comparison raises important questions:

- Are economic elites today wielding disproportionate influence over democratic systems?

- How do technological advancements, particularly social media, create new tools for authoritarianism?

- Can modern democracies learn from the mistakes of the Weimar Republic to resist similar trends?

Conclusion

The dismantling of the Weimar Republic offers a sobering reminder of how democracy can be eroded from within.

However, it also highlights the importance of institutional resilience and civic engagement in countering authoritarian trends.

While the U.S. faces different challenges, the interplay of legal exploitation, crisis manipulation, media control, and economic influence echoes historical patterns.

Recognizing these trends is the first step toward safeguarding democratic institutions against contemporary threats.